The walls would be plush, like a Las Vegas lounge, speckled with hundreds of small LED lights programmed to change color. The vibe would be cozy and modern, intended to “create a nest,” its designer says: “A comfortable and friendly egg, which would feature materials and colors stemmed from a fetal universe.”

The best features would, of course, be the windows, generously large for expansive views of the Earth below and the universe beyond because star gazing is at the center of Philippe Starck’s latest creation. Instead of designing another avant-garde piece of furniture, or a luxury yacht or a gleaming hotel, the French architect and designer is working on the interior of a commercial space station that NASA hopes one day would replace the International Space Station.

For more than 20 years, the ISS has served as a continuously inhabited foothold in low Earth orbit, a way for space agencies around the world to study how humans live off the Earth for extended periods. A total of 19 countries have sent astronauts there, binding them into an international consortium that has transcended politics and the geopolitical tensions that have roiled relationships on Earth. To build the ISS, the United States and Russia combined forces with Canada, Japan and the European Union. The program has been such a profound tool of diplomacy, as well as science and engineering, that many in the space community think it should be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. At the very least, they think the life of the ISS should be extended. And late last year, the White House backed NASA’s plan to keep the ISS operating to 2030.

But it’s not clear that that the station will last that long. In recent years, it has sprung a series of leaks and has been rattled by errant thruster firings that have sent it spinning wildly. Despite its incredible durability, it cannot survive in the harsh vacuum of space forever. The extreme hot and cold temperatures take their toll. So do the bits of micrometeorite debris that the space station dodges a few times a year and occasionally gets hit. At some point, it will reach the end of its life, and NASA and its partners will be forced to coordinate its demise by deorbiting it to Earth and crashing it into the ocean.

Knowing that day may soon come, NASA is racing to find its successor. But the space agency won’t be building it. After investing billions of dollars into the ISS, NASA cannot afford to build another space station in Earth orbit, especially as it is embarking on an effort to return humans to the moon, under a program called Artemis. Instead, it is looking to the private sector to develop next-generation habitats that would be owned and operated by the companies, not NASA.

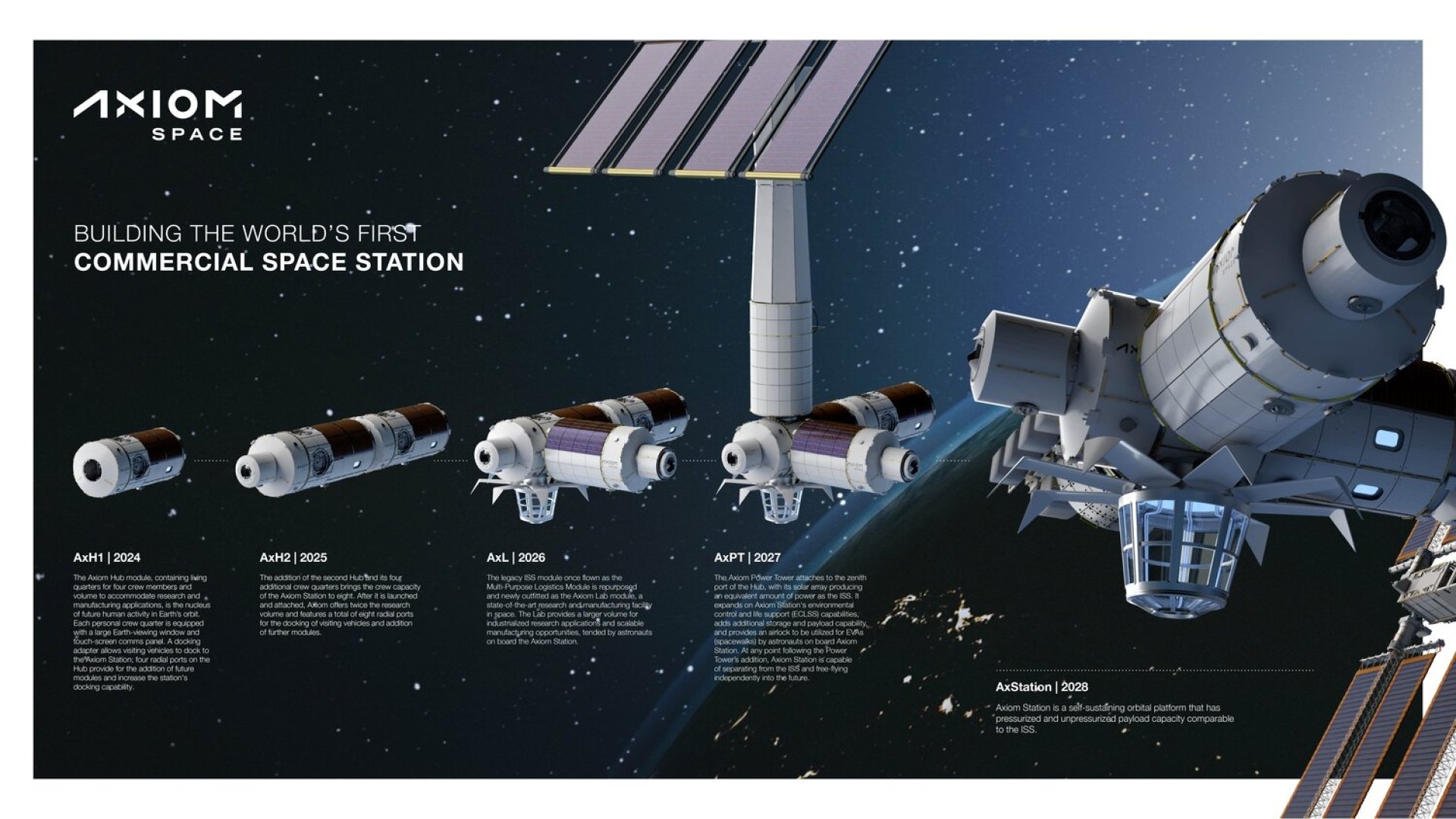

The space agency has recently taken the first major steps in that direction, reaching an agreement with Axiom Space, a Houston-based company that has hired Starck, to send a module of its space station to attach to the ISS as a test bed as soon as 2024. Late last year, NASA awarded contracts to develop commercial space stations, worth $415.6 million combined, to Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin, Nanoracks, which helps companies fly science experiments and other payloads to the ISS, and Northrop Grumman, the longtime defense contractor.

The contracts are yet another sign that NASA is willing to place enormous bets on the growing commercial space industry, which has been eroding governments’ long-held monopoly on space activity. Driven by the investments and ambitions of the so-called “space barons,” Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos and Richard Branson, who have invested heavily into their space ventures, the industry has taken off.

Musk’s SpaceX in particular has demonstrated the commercial ventures can be successful and help bolster NASA. For years SpaceX has flown cargo and supplies for the space agency to the ISS. NASA has expanded that public-private partnership, allowing SpaceX to fly its most precious resources—its astronauts—to the space station as well. The company also recently won a $3 billion contract to develop the spacecraft that would ferry astronauts to and from the surface of the moon.

NASA is now extending this relatively new model to space stations, hoping the private sector can take on an even greater task—building destinations in space—that presents a host of even greater challenges. And it comes as some are warning that unless NASA and its partners can build the stations quickly, it could be faced with the ignominious prospect of the ISS retiring before its successor is ready. That would leave the United States with nowhere to send its astronauts, a problem exacerbated by the fact that China has started to build a station of its own.

“I think it would be a tragedy if, after all of this time and all of this effort, we were to abandon low Earth orbit and cede that territory,” former NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine told a Senate panel in 2020.

The cost of a new space station is enormous. And so are the technical and engineering hurdles. Keeping people alive and healthy in space requires enormous vigilance: making sure they have enough to eat and drink; that they get along and don’t kill each other; that they don’t get hit by a micrometeorite; that they can communicate reliably to people on the ground; that they can handle sickness or injury on their own; or repair any number of problems for extended periods. It is such a daunting task that it’s something of a miracle that after more than two decades there has not been any major incidents on the ISS.

Whether the private sector can build commercial stations and operate them safely, then, remains to be seen. And if it can’t do that before the ISS finally reaches the end of its life, NASA would have a gap that would be even more severe than the period after the Space Shuttle was retired in 2011 with no alternative to launch its astronauts from United States soil. Instead, Russia flew NASA’ astronauts to the ISS, and charged a hefty price for the service, nearly $90 million a seat, before SpaceX restored human spaceflight for NASA in 2020.

“ISS won’t last forever & incentivizing the private sector to begin follow-on capabilities are needed now,” Lori Garver, who served as NASA deputy administrator in the Obama administration, warned on Twitter in 2020. “This concept isn’t hard. Have we learned nothing in the last 10 years?”

On the outside, Axiom’s station may look like the ISS, with solar arrays, docking ports, but the inside would be a world apart from the government-funded station. It would feature the “largest window observatory every constructed for space,” the company says. And unlike the at-times clunky and cluttered ISS, designed purely for function and astronaut survival, Axiom’s station would have the attributes of a hotel, a touch of Starck’s style and eye toward comfort mixed in.

“We want the customers to have this great, comfortable, luxurious feel,” Michael Suffredini, Axiom’s co-founder, told The Washington Post. “We’re even looking at how we cook food on orbit…to make the food a little more tasty.”

Blue Origin’s station, called Orbital Reef, would also have large windows, and the initial configuration would be expansive, about 90 percent of the interior volume of the ISS, with room for nearly a dozen astronauts. And it would have the ability to grow over time, as more modules get added. The station “will provide anyone with the opportunity to establish their own address on orbit,” Blue Origin says. The company has teamed up with a host of aerospace giants—Sierra Space, Boeing, Redwire Space, Genesis Engineering and Arizona State University—that would have the station ready by the second half of the decade.

Bezos has moved slowly and steadily into the space business, his passion since he was five years old and watched Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walk on the moon. That, as he has said, was a “seminal moment” for him, that inspired him to found the company—“blue” for the “pale blue dot” that is Earth, “origin” for where humanity began—more than 20 years ago.

Bezos has said his space venture is “the most important work I’m doing.” Recently it has flown a series of people to the edge of space and back on suborbital tourist jaunts, allowing paying customers a few minutes of weightlessness and views from more than 60 miles high. The company is also building a massive rocket called New Glenn, that could reach orbit, and spacecraft that would land astronauts on the moon

But it has even more ambitious goals; Bezos says he wants “millions of people living and working in space.” In the long-term, hundreds of years from now, Bezos envisions massive space stations large enough to hold entire cities, even mountain ranges, plucked from the pages of science fiction. These stations would house thousands of people at once with climate conditions controlled by humans.

“These are really pleasant places to live,” Bezos said in 2019, during a speech in Washington. “This is Maui on its best day all year long. No rain. No storms. No earthquakes.”

That dream is a long way away and may never be realized. In the meantime, the company is partnering with Colorado-based Sierra Space to build the Orbital Reef space station. Calling it “a mixed use business park in space,” the companies say it would provide “a vibrant, growing business ecosystem in low Earth orbit that will generate new discoveries, new products, new forms of entertainment and global awareness of Earth’s fragility and interconnectedness.”

One of the key components of the station are habitation modules that inflate like balloons once they reach orbit. Instead of fixed structures, these habitats can be packed into the nose cone of a rocket and then expand in space, allowing them to be transported to orbit in a single launch.

Nanoracks also plans to use inflatable modules on its station, called Starlab. Built in conjunction with Lockheed Martin, Starlab would feature a laboratory, named for George Washington Carver, the famous scientist, where companies and countries could conduct experiments.

NASA would be one of the key customers for the commercial stations. But the companies believe there will be a strong demand from others as well that would support multiple private space stations. Countries with growing space ambitions, like India and the United Arab Emirates, could be looking for a destination for their astronauts. There are companies that would want to do research in space. Entertainment could also become a revenue source. Last year, Yulia Peresild, a Russian actress and film producer, Klim Shipenko, flew to the ISS to film scenes for a movie called, “The Challenge.” Peresild plays a doctor hoping to save the life of a crew member in space. NASA has also said it is working with Tom Cruise to shoot scenes for a movie on the ISS.

Commercial space stations could change what it means to be an astronaut and who gets to become one. The companies think there would be a high demand for private citizens to go to space. Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic have already sold dozens of tickets on their suborbital spacecraft. Blue Origin even auctioned off one seat for $28 million to a crypto entrepreneur. SpaceX flew a crew of four private citizens in orbit around Earth for three days last year in its Dragon spacecraft.

While it’s developing its space station, Axiom Space it working with a number of private citizens to go to the ISS on flights chartered by the company on a SpaceX rocket. The first flight, scheduled for February, would take three wealthy businessmen, who are paying $55 million each, for about a week on the station. They’d be accompanied by Michael Lopez-Alegria, a former NASA astronaut, who now serves as an Axiom vice president. The company is planning another private-astronaut mission, scheduled for later in the year, with Peggy Whitson, the decorated former NASA astronaut who was the first female commander of the ISS, to serve as the guide.

In the 200s, Russia flew a number of private citizens to the space station for the price of about $20 million each. Until recently, though, the practice was prohibited by NASA, which feared they would interfere with the astronauts. The policy was changed, though in 2019, in an effort to boost the commercialization of space.

“This is the very beginning,” Jeffrey Manber, CEO of Nanoracks, said. “We’re going to enter the next decade, where you have multiple private space stations in a robust public-private partnership with NASA.”

Perhaps. But space is hard, and failure is as much a part of the history of exploration as triumph. Even behemoths such as Boeing have struggled. While SpaceX has successfully launched several astronaut crews to the ISS for NASA, Boeing has yet to have a successful flight of the capsule it is developing for the same purpose.

On its first flight, a test without any astronauts on board in December 2019, the autonomous Starliner capsule ran into trouble shortly after it reached orbit. Its on-board computer was 11 hours off, making it think it was in an entirely different point in the mission. Then another software problem could have caused a collision as the service module separated from the crew capsule. Boeing had to cut the mission short and bring the capsule back without docking with the ISS, one of its primary objectives.

The redo of the uncrewed test flight last year didn’t even get off the ground. While it was preparing to launch, officials noticed that several valves in the service module were stuck. Now, that flight may not happen until at least May, and the first flight with astronauts onboard may not come until the end of the year at the earliest, which would be several years behind schedule.

Given that track record, it is not clear that the commercial space industry is up to the more daunting task of building and operating space stations. Space is rough. There are thousands of bits of debris whirling around in orbit at 17,500 m.p.h. so that even a small piece can cause catastrophic damage. From time to time, the ISS has to maneuver to avoid getting hit, and sometimes it does. In 2016, a piece of debris cracked a window. Then last year a piece hit the station’s robotic arm, leaving a small puncture, like a bullet hole.

Russia last year added to the dangerous clutter in space when it fired a missile and blew up a dead satellite as target practice. It was seen as a warning to the United States and others that it could take out key satellites in orbit. But it caused a massive cloud of debris that threatened the ISS, and forced the astronauts, including two Russian cosmonauts, to seek shelter. The crew out on their spacesuits, boarded their spacecraft and waited for the worst. If debris hit the station, the astronauts were ready to abandon it for home.

Last summer, the ISS was taken on a wild ride when the thrusters of a newly installed Russian module started firing by mistake. It spun the ISS one and a half times, leaving it upside down before crews could get it back to its normal orientation. The astronauts were never in danger, NASA said, but a flight director in Houston said that he was thrilled that the solar arrays didn’t snap off.

There are less dramatic mishaps as well. After more than 20 years in orbit, things break, even the toilet. The batteries need to be replaced. Every once in a while, the ISS springs a leak, like the one recently that was so small the astronauts had a hard time finding it. They were able to isolate it to the Russian segment of the station, where an enterprising astronaut opened a bag of tea and watched how the leaves floated to a barely perceptible hole.

While the partners on the ISS are working to keep it going, the Chinese are building a brand new station. Last year, it launched the first of three modules and intends to complete it by the end of 2022. Called Tiangong, or “Heavenly Palace,” the station would be home to three astronauts, and China plans to keep it in operation for a decade.

It is part of a broader space program that included the first landing of a robot on the far side of the moon in 2019. Last year, it became only the second nation, after the United States, to land and operate a rover on Mars. Viewing China as a threat, the Trump administration took a very hawkish tone when talking about its space ambitions. In a speech calling for NASA to send astronauts back to the moon, former Vice President Pence warned that China was trying “to seize the lunar strategic high ground and become the world’s spacefaring nation.”

While it has sought to dismantle virtually every remnant of Trump’s legacy, the Biden White House has embraced its tough stance against China. Bill Nelson, who serves as the NASA administrator for the Biden administration, has called China “a very aggressive competitor” that is challenging American leadership. And he recently warned: “Watch the Chinese.”

The intent of such talk may be political. Compared to other agencies, NASA’s budget is tiny—less than one-half of 1 percent of the federal budget. Over the next few years, much of it will be tied up in its “Artemis” program to return astronauts to the moon, leaving little for space station development. So Nelson, the former Democratic Senator from Florida, knows he needs more money from his former colleagues in Congress.

His predecessor agrees.

“We are not ready for what comes after the International Space Station,” Bridenstine, the NASA Administrator during the Trump administration, said during a Senate recently. “Building a space station takes a long time, especially when you’re doing it in a way that’s never been done before.”

NASA this year requested $101 million for the program that would develop private space stations, but Bridenstine and other have said that is not nearly enough. In his written testimony, he said Congress needed to appropriate $2 billion annually to the effort.

While NASA lobbies Congress for more money, and the companies work to develop their commercial stations, the ISS keeps humming along, orbiting the Earth every 90 minutes, as it has for years, a marvel of engineering that continues to set new records for human space exploration. Another one is set to fall shortly.

About two weeks before he returns to Earth in March, NASA astronaut Mark Vande Hei would break the America spaceflight duration record set in 2016 by Scott Kelly. In all, the former Army Colonel will have spent a total of 353 days on the station—just short of a full year but 13 more days than Kelly and any other American. During his time on the orbiting laboratory, he will have performed hundreds of experiments for scientists on the ground. But in some sense, the real experiment isn’t anything in a test tube. Rather, it’s him, his body—brain, bones and blood—that doctors and scientists will study to see what sort of effect space had on him, and what clues it might hold as NASA prepares to send humans on long-duration missions to the moon and Mars.

As it looks to reaching out further into the solar system, NASA hopes Vande Hei’s record, too, will fall. If it does, it won’t be on a station that built by NASA. From now on, it plans to be a tenant in low Earth orbit, not the landlord.

Author

Staff Writer at The Washington Post, covering the defense and space industries; Author of "The Space Barons: Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos and the Quest to Colonize the Cosmos"

Science and Technology Innovation Program

The Science and Technology Innovation Program (STIP) serves as the bridge between technologists, policymakers, industry, and global stakeholders. Read more