The past few decades have witnessed the largest changes to the space establishment since the Cold War. Between Sputnik 1 and SpaceX Falcon 9, we have seen more nations establish their own defensive space commands, diversify their space technologies, and even demonstrate potentially destructive capabilities for the world to see.

What’s more is that space exploration is no longer a domain reserved for wealthy nations alone. Today, private stakeholders have also earned (or paid for) a seat at the table. Billionaires including Paul Allen, Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos and Richard Branson at the helm of companies such as Stratolaunch Systems, SpaceX, Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic, respectively, have disrupted a market long dominated by defense contractors. One thing is clear: space has matured into a domain driven by a greater number of actors—be it nations, private entities, or non-traditional actors—and is now more congested, contested, and competitive than ever before.

We no longer need a telescope to see the critical importance of space. But while much attention has been paid to the geostrategic and economic significance of space, perhaps the most foundational area has been largely left on the backburner: space governance. In the current international political climate, once-adequate multilateral agreements and treaties have repeatedly proven ineffective at managing international space activities. The current global space governance framework has been slow to take evolving state and industry practices as well as technological changes into consideration, namely around issues of celestial resource use and space militarization. The growing number of non-traditional players warrants a need for additional, if not revised, legal measures to ensure stronger global space governance and the safety and sustainability of space for the future ahead.

To understand the future ahead, however, we need to consider the state of space governance now. Here, we outline the current legal systems which collectively comprise the global space governance system while critically identifying and explaining the deficiencies within those systems. In doing so, we will show possible paths to stronger global space governance to ensure the safety and sustainability of space for the future ahead.

Global Space Governance: What Does it All Even Mean?

The term “global space governance” refers to a collection of international, regional, or national laws as well as regulatory institutions and actions, manners, and processes of governing or regulating space-related affairs or activities. It also includes the instruments, institutions, and mechanisms; national laws, regulations, technical standards, and procedures; codes of conduct, and confidence building measures between space-faring actors; all of which are discussed, formulated, and implemented at various levels of government. Collectively, these measures allow for the formulation, compliance monitoring, and enforcement of space activities. But to what extent are these measures effective at responding to Chinese rocket debris from falling down to Earth or preventing Russians from testing projectile shooting satellites? The answer: not well enough.

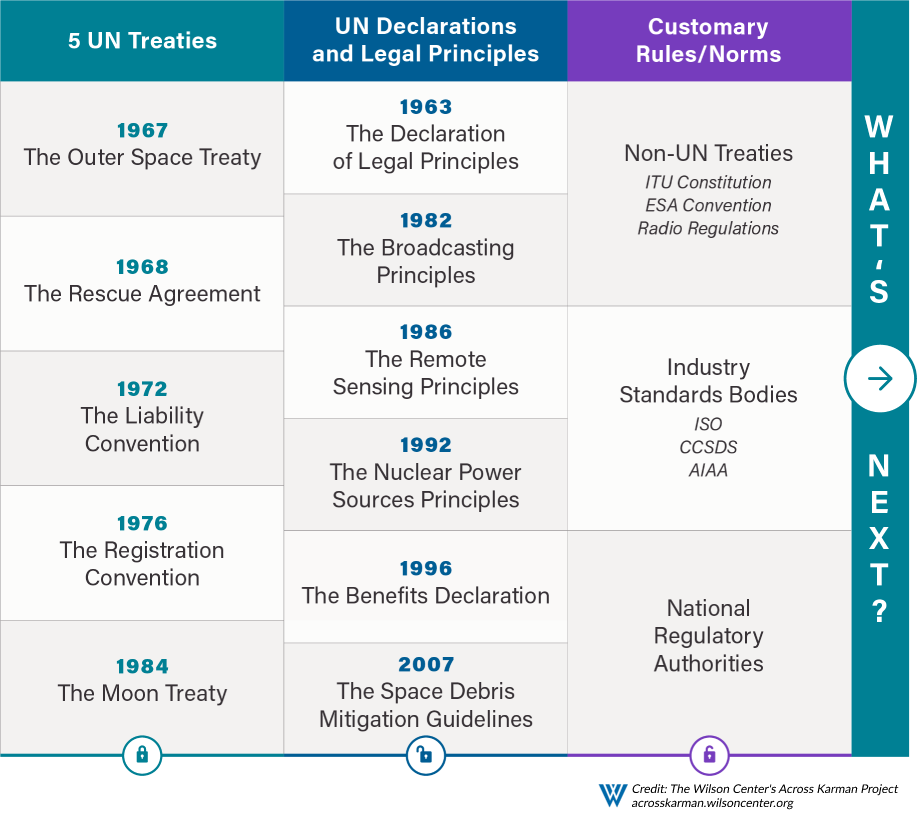

Generally, international space law falls into two categories: 1) binding or normative instruments such as treaties, standards, and national regulations, and 2) non-binding agreements which are used to convey voluntary, non-normative and/or aspirational ideals that may be too difficult to achieve international consensus on. These two types of agreements largely work in tandem to make up the global space governance framework that exists today.

Global space governance was born out of the Cold War era, where only a few actors—namely the United States (U.S.) and the Soviet Union—had access to spaceflight or launch capabilities. In today’s world, however, 72 nations claim to possess space agencies and 14 are capable of orbital launch. Unfortunately, this means that low-to-middle income countries have been largely excluded from writing the rules that are still in place over half a century later. Furthermore, the five foundational United Nations (U.N.) space treaties—which make up the backbone of the global space governance framework—are products of their time which explains their particular emphasis on preventing the militarization and colonization of space. With the rapid pace of space development, however, the future of space governance will need to encompass additional threats brought on by novel changes to the global order. This will prove to be a delicate, if not tricky, balancing act between encouraging democratization, boosting commercialization, and containing militarization.

The UN and the Foundation of Global Space Governance

UN Office of Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA)

For over half a century, the U.N. has been the primary facilitator of global space governance and law. In 1958, the U.N. Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA) was established to support governments in building legal, technical, and political infrastructure to support global space activities. In addition to helping states understand space law and develop their own national space policy in line with the established global governance framework, UNOOSA maintains a registry of objects launched into Outer Space and plays an essential role in the formation of additional international organizations to address specific issue areas in space regulation.

In the 1960s, for example, increased public and private use of geosynchronous orbit (GEO) for telecommunications and other services gave rise to the need for an international regulatory system agreed upon by sovereign stakeholders. As a result, UNOOSA identified the International Telecommunications Union (ITU), originally established in 1865 to create international radio communication standards and tasked it with becoming the U.N.'s specialized agency for information and communication technologies. Through the implementation of radio regulations and regional agreements, the ITU ensures that radio-frequency spectrum and associated satellite orbits are used equitably, efficiently, and economically by states and prevents physical and electromagnetic interference in geosynchronous orbit. To achieve this, the ITU assigns GEO slots to U.N. Member states by considering orbital parameters (west or east degrees longitude), type of frequencies used, and covered regions (or footprint). From there, Member states look to national regulations to license their use of assigned GEO slots. Another responsibility of UNOOSA was establishing the International Asteroid Warning Network (IAWN) and the Space Mission Planning Advisory Group (SMPAG) in 2013 to coordinate global efforts to identify and respond to Near-Earth Objects (namely, asteroids) that threaten Earth.

UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS)

Approximately one year after the launch of Sputnik 1, the U.N. Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) was formed as an ad hoc Committee in the U.N. and was later made permanent in 1959. With UNOOSA providing secretariat services for the Committee, COPUOS was created “to govern the exploration and use of space for the benefit of all humanity: for peace, security and development,” ultimately becoming responsible for the creation and implementation of the five UN treaties related to outer space activities, principles, as well as other related international agreements (as each pertains to space).

COPUOS and its 95 member states discuss issues including the regulation of space debris, the extraction of space resources, the standardization of small satellites such as CubeSats, the nuclearization of outer space, and threats posed by asteroids and other types of space rock, among other areas requiring clever and purposeful space law. These efforts are divided between COPUOS’ two subcommittees—the Scientific and Technical Subcommittee, and the Legal Subcommittee—and meet annually to discuss issues relating to the major space treaties and international mechanisms for cooperation in space.

The Five UN Space Treaties

As previously mentioned, a series of treaties adopted by the U.N. General Assembly (UNGA) form the foundation of the global space governance system. The first and most significant of these treaties is the “Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies,” more commonly known as the Outer Space Treaty or OST for short (1967). The Outer Space Treaty is considered the most comprehensive space treaty and provides the basic framework for international space law, namely: the exploration and use of outer space for peaceful purposes by all States for the benefit of mankind (Art. I); the outlaw of national appropriation or claims of sovereignty of outer space or celestial objects (Art. II); a ban on the placement of weapons of mass destruction in orbit or on celestial bodies (Art. IV); that astronauts should be regarded as the envoys of mankind (Art. V); and that States are required to supervise the activities of their national entities (Art. VI).

Although the Outer Space Treaty is the cornerstone of international space regulation (with 111 ratifications and 23 signatories), gaps in governance were evident immediately after its adoption. The primary weakness of the OST is that it only addresses the non-placement of weapons of mass destruction and not conventional weapons in space. While placing a weapon in space would be deemed an act of war universally, the OST’s lack of scope is particularly important in the modern-day context where ground-based weapons such as anti-satellite (ASAT) weapons exist to target space assets. The OST’s vague language about how states manage their space resources raises additional issues, as States have taken it upon themselves to define terms based on their own national priorities and interests. Besides competing national priorities and interests in space, many definitions of terms were written before space technologies advanced. Definitions of “space weapon,” “defensive” or “peaceful” use of outer space, and “astronaut” have all evolved and changed since the original treaty was written.

To supplement these gaps, four additional treaties were created, but were largely unsuccessful in garnering enough support and mitigating the deficiencies of their predecessors. Expanding on Articles 5 and 8 of the OST, the second foundational U.N. space treaty “The Agreement on the Rescue of Astronauts, the Return of Astronauts, and the Return of Objects Launched into Outer Space'', termed the Rescue Agreement (1968), states that States must take measures to rescue and assist astronauts in the event of an accident, distress, or emergency landing, and return them to their launching state in addition to assisting launching states with recovering space objects that return to the Earth outside the native state of launch. Even though the Rescue Agreement is clear on the status of astronauts as “envoys of mankind,” an opportunity for other States to test the Agreement’s efficacy—or assist an astronaut in distress has not yet occurred to help when one state’s astronauts or cosmonauts were in distress.

The third foundational U.N. space treaty, “Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects,” termed the Liability Convention (1972), outlines the liability of Launching States for damage caused by their space objects both on the Earth or in space as well as procedures for the settlement of claims for damages endured. This means that states remain responsible for any space assets launched from their territory, which infers that the same states are liable for any damages should there be an accident. According to the Liability Convention, claims against damage or destruction are brought by a state against a state, irrespective of who caused the incident, whether it was a commercial actor or a State space agency. According to most national legal instruments, an individual or an industry could initiate a lawsuit against another individual or industry, but regarding international space law, the Liability Convention determined that states are ultimately responsible even if an incident is caused by a private actor. The Liability Convention has only been invoked one time, in 1978, when the USSR’s Cosmos 954 satellite accidentally reentered Earth’s atmosphere, scattering around 50 kg of radioactive uranium-235 over northern Canada. Although this area was sparsely populated, several residents were accidentally exposed to radiation before a major recovery campaign succeeded in sweeping a total area of 124,000 square kilometers over the course of almost one year (Karacalıoğlu, 2014).

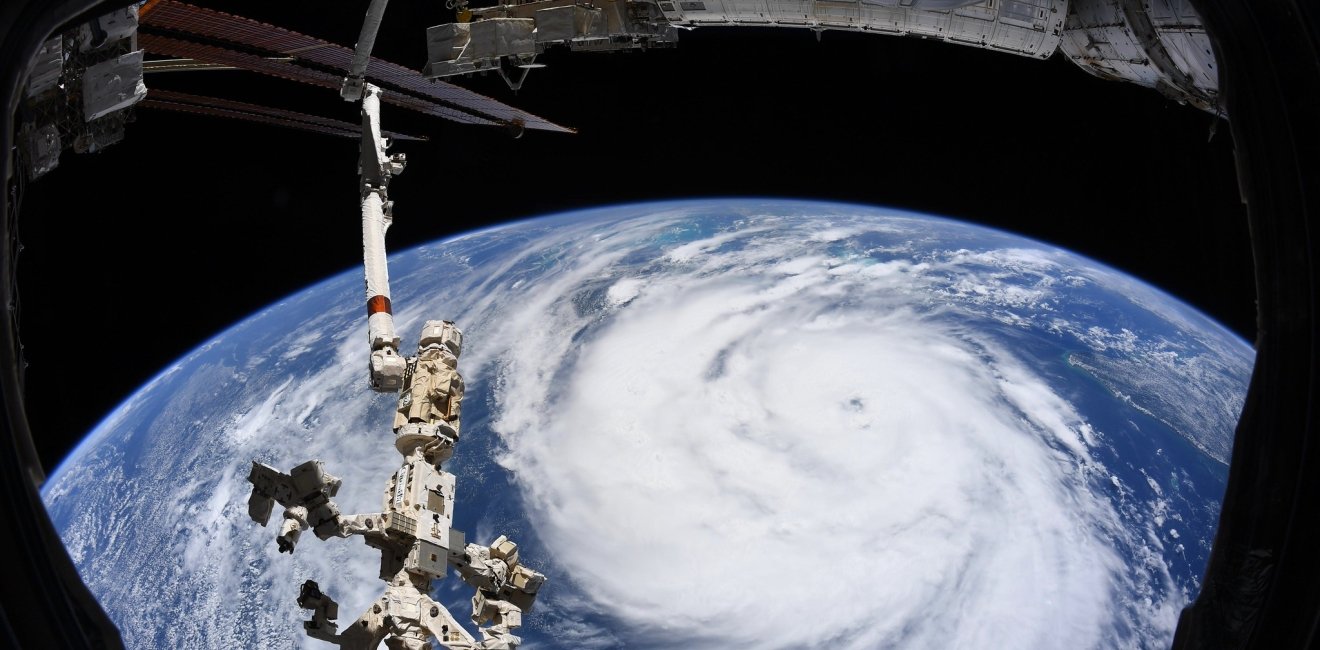

Since the 1950s, debris have been accruing in space. NASA estimates there are roughly 22,000 objects larger than 10cm in diameter in near-Earth orbit. The Liability Convention outlines the liability of Launching States for damage caused by their space objects both on the Earth or in space. Credit: NASA/JSC/Orbital Debris Program Office

The fourth treaty, “Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space,” termed the Registration Convention (1976), has a straightforward objective of registering space objects. Building on Article VIII of the OST which deals with the registration and jurisdictional aspects of launched outer space objects, the Registration Convention states that launching States must maintain a registry of their space objects and provide the U.N. with information on the objects they launch into outer space. This treaty is important from the standpoint of both the Rescue Agreement and the Liability Convention in that without the registration of space objects, no State could ever be held accountable should an incident occur. Its purpose, therefore, is to identify which State’s object it was, as well as to fix liability and compensation on states for damage or destruction.

The fifth treaty, “The Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies,” termed the Moon Treaty (1984), has received the least support by Member nations for its reaffirmation and elaboration of Outer Space Treaty provisions in the context of appropriating and exploring the Moon and exploiting its resources. The Moon Treaty states that the Moon shall be used by all states “exclusively for peaceful purposes,” and that “(A)ny threat or use of force or any other hostile act or threat of hostile act on the moon is prohibited.” Additionally, it prohibits the placement or use of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) on the Moon, as well as the “establishment of military bases, installations, and fortifications, the testing of any type of weapons and the conduct of military maneuvers” (U.N. Office for Disarmament Affairs, 1979).

The Five Sets of UN Principles

Following the ratification of the five U.N. foundational space treaties—whether with great or little support—the international space law community transitioned to the development of voluntary consensus principles and guidelines for space operations, debris mitigation and space sustainability. In addition to the five general multilateral treaties, the U.N. oversaw the drafting and formulation of five sets of principles adopted by the General Assembly, including the Declaration of Legal Principles. Although such influential voluntary international guidelines may contain more detailed, challenging, and aspirational goals, they are non-binding.

Apart from the “Declaration of Legal Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space,” the four additional declarations were

- “The Broadcasting Principles,” or Principles Governing the Use by States of Artificial Earth Satellites for International Direct Television Broadcasting;

- the “Remote Sensing Principles,” or Principles Relating to Remote Sensing of the Earth from Outer Space;

- the “Nuclear Power Sources” Principles, or Principles Relevant to the Use of Nuclear Power Sources in Outer Space; and

- the “Declaration on International Cooperation in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space for the Benefit and in the Interest of All States, Taking into Particular Account the Needs of Developing Countries.”

Conference on Disarmament (CD)

Apart from UNOOSA and UNCOPUOS and their mechanisms, another dedicated forum established to debate and negotiate arms control and disarmament agreements, is the Conference on Disarmament (CD). While not formally a U.N. organization, it is connected to the U.N. through a personal representative of the U.N. Secretary General and considers recommendations of the UNGA as well as proposals from its members. The CD is responsible for successfully negotiating a slew of non-proliferation treaties, most notably Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons and the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT).

The CD has a comprehensive mandate to cover, including negotiating and discussing the “cessation of the nuclear arms race and nuclear disarmament; prevention of nuclear war; prevention of an arms race in outer space; effective international arrangements to assure non-nuclear weapon States against the use or threat of use of nuclear weapons; and new types of weapons of mass destruction.” However, due to member-state gridlock, not enough substantive discussions, and debates on critical measures such as the Fissile Material Cut-off Treaty (FMCT), Prevention of Arms Race in Outer Space (PAROS) and nuclear disarmament have taken place.

Non-UN Measures

Binding national governance and enforcement mechanisms promote space security commensurate with each state's unique interpretation of international common space law, accepted best practices and expected norms of behavior. However, disparities in each state's interpretations may at times lead space operators to adopt “flags of convenience,” either to avoid costly analyses, designs, or operational mandates, or to otherwise circumvent tougher regulations. Consequently, non-binding voluntary industry best practices and self-governance tend to be favored by space operators and commercial industry.

More recently, the U.N. issued additional resolutions on the reduction of space threats, such as Resolution A/RES/75/36 in December 2020, “Reducing space threats through norms, rules and principles of responsible behaviors.” The U.N. General Assembly has also encouraged states to implement transparency and confidence-building measures (TCBMs) regarding space exploration, including information exchanges, facility visits, and international cooperation. While the U.N. encourages international cooperation, the process for defining and implementing the terms of that cooperation is left entirely to the states involved. Bilateral and multilateral agreements have facilitated international cooperation and legal frameworks for participating states in their space activities and projects. In the last thirty years, states have also relied on non-binding international agreements to generate rules and regulations in space, to generate norms without inhibiting the diversity of interests in space.

Why Is New Governance Necessary?

In an age where space is evolving and developing more rapidly than intergovernmental organizations can keep up, it is abundantly clear that the current global space governance framework—a product of the Cold War—is no longer adequate. In its current state, the global space governance framework excludes many space activities and allows actors to operate under wide-ranging and often conflicting interpretations of existing agreements. While there have been many attempts to improve the governance framework, progress in this area has stagnated, in large part due to diplomatic impasses between international actors and has negatively impacted the sustainable development of space.

Of the five international agreements previously mentioned, the Outer Space Treaty (1967), Rescue Agreement (1968), the Liability Convention (1972), and the Registration Conventions (1974) require substantial clarification in order to apply many of their principles to new space activities and issues, such as satellite servicing, space traffic management, tourism, or space debris mitigation. The Moon Treaty (1979) has too few signatories to be effective altogether. Although countries have attempted to improve or complement these agreements over the years, no new multilateral agreements have been produced since the 1970s. In their place, non-binding norms have emerged in large part due to the ease by which they can be created and set into effect, however effective or ineffective they may be.

Often slow to action, limited in authority, and bogged down by political deadlock, international bodies like COPUOS—and more indirectly, UNOOSA—which were established to advance global space governance, are failing to further their mission. While this has not dissuaded spacefaring nations from proposing new multilateral policies addressing evolving uses of space through international fora, important technological advancements—such as the rapid advancement of the commercial space sector—are often overlooked. This raises concerns, namely because private entities are not bound by the Outer Space Treaty or any of the other agreements. Another obstacle of note is that different States have different priorities when it comes to transparency and confidence building measures (TCBMs) and often, competing economic and military interests tend to stall those efforts.

Seeking Strategic Advantage: How Geopolitical Competition and Cooperation are Playing Out in Space

As our dependency on space grows, what are the implications for the world’s critical infrastructure? Do risks to space capabilities threaten global economic development and international security? Former NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine and experts from Aerospace Corporation discuss the future of governance in space in this event hosted at the Wilson Center.

WatchWhile easier to agree upon in the short-term, passive support from various states and private actors on nonbinding agreements—such as the UNGA principles as well as the Code of Conduct for Outer Space Activities—will not hold in the long-run. One thing is clear: multilateral efforts have not proven completely effective, and more is needed to provide order as new space interests are pursued.

It’s clear that the most significant development in this domain since the space race has been the growth of the commercial space sector. However, with expanded space activities comes increased competition among various actors, necessitating new and different governance structures.

Recent trends in the preferential creation of domestic policies over international agreements reflects the growing value of commercial space and the stagnation of international space governance, as exemplified by U.S.’ development of a new National Space Policy and series of Space Policy Directives — spanning human space exploration, commercial space regulations, national space traffic management, Space Force creation, cybersecurity in space, and space nuclear power and propulsion — to address pressing international challenges. Alongside the Artemis Accords, these documents aim to establish modern international law and norms beyond the Cold War-era U.N. space treaties.

But despite the bold spearheading of national laws aligned with international space commitments by countries such as Russia and the U.S., there is little policy convergence among existing nations’ domestic space policies. This lack of coordination in turn hinders the development of commercial space activities and poses threats to the use of space as a global commons, especially with regard to satellite servicing and space traffic management. As highlighted in this 2019 article, the U.S. should focus on creating effective bilateral agreements with like-minded allies to foster space sustainability and overcome international gridlock as bilateral agreements have historically positively reinforced global governance behavior.

One area ripe for both norms-based and formal international collaboration is space situational awareness (SSA) and space traffic management (STM). New agreements on SSA and STM would allow greater transparency on different actors’ activities in space, and would further reduce concerns about dual-use technologies, make on-orbit operations more precise, and ease concerns related to orbital debris management. Furthermore, it is essential that better traffic management practices and regulations be initiated to prevent incidents in space. For instance, though the U.S. Department of Defense and various countries and commercial actors currently engage in SSA cooperation through memoranda of understanding, an increasing amount of space activity is straining the Defense Department’s ability to provide safe and actionable data. More formal cooperation between the U.S. and its allies and partners is needed, potentially through support from COPUOS.

Another key challenge which would benefit from both norms-based and formal international collaboration is space debris mitigation. Novel agreements on space debris mitigation should follow guidance from existing guidelines of leading space agencies—such as the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee’s (IADC) Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines— AND be adapted and formalized as official treaties and executed through national regulations. It is important to highlight that the full value of space cannot be realized if the challenges posed by space debris are not addressed at the level of binding agreements, which would legally mandate states to comply by mutually agreed-upon rules.

Of the many challenges facing global space governance—growing space debris, over-populated orbits, radio frequency interferences, issues of spectrum allocation, and the development of counter-space capabilities—none can be addressed without reinstating intergovernmental bodies with the ability to develop an effective outer space regime. Outdated provisions whose definitions and vague language are left up to the interpretation of states must be reviewed and new rules of engagement need to be developed. Despite all political obstacles, decision leaders must give priority to the development of effective international space law first and foremost by committing to strengthening international dialogues, encouraging openness, greater transparency and information-sharing, and avoid pushing national agendas in lieu of ensuring space remains a global commons.

Note

For the current status of International Agreements relating to activities in outer space, visit the U.N. Office of Outer Space Affair's Status of International Agreements relating to Activities in Outer Space.

References

Bansal, Nitansha. “Why Space Governance Now?” Observer Research Foundation, November 20, 2017.

Blount, P.J. “Space Security Law.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Planetary Science. Oxford University Press, June 25, 2018.

Cabral, Peter. “The Game Has Changed: Why We Need New Rules for Space Exploration.” Singularity Hub, March 3, 2021.

Johnson, Kaitlyn. “Key Governance Issues in Space.” Center for Strategic and International Studies, July 21, 2021.

Morozova, Elina, and Yaroslav Vasyanin. “International Space Law and Satellite Telecommunications.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Planetary Science. Oxford University Press, December 23, 2019.

Mosteshar, Sa'id. “Space Law and Weapons in Space.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Planetary Science. Oxford University Press, May 23, 2019.

Nucera, Gianfranco Gabriele. “International Geopolitics and Space Regulation.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Planetary Science. Oxford University Press, May 23, 2019.

Oltrogge, Daniel L., and Ian A. Christensen. “Space Governance in the New Space Era.” Journal of Space Safety Engineering. Elsevier, July 1, 2020.

Pelton, Joseph N., and Ram S. Jakhu. “Global Space Governance: Key Proposed Actions.” Institute of Air and Space Law, McGill University, 2017.

Rajagopalan, Rajeswari Pillai. “Space Governance.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Planetary Science. Oxford University Press, August 28, 2018.

Routh, Adam. “Near-Earth Space Governance Is All about the Money.” The Space Review, November 11, 2019.

Silverstein, Benjamin, and Ankit Panda. “Space Is a Great Commons. It's Time to Treat It as Such.” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, March 9, 2021.

Sinclair, Michael. “What You May Have Missed in the New National Space Policy.” The Brookings Institution, December 17, 2020.

Smuclerova, Martina. “Use of Outer Space for Peaceful Purposes.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Planetary Science. Oxford University Press, April 26, 2019.

Space Foundation Editorial Team. “Space Policy Directives (SPDs).” The Space Foundation, February 10, 2021.

Tucker, Patrick. “Nobody Wants Rules in Space.” Defense One, May 6, 2021.

van Eijk, Cristian. “Sorry, Elon: Mars Is Not a Legal Vacuum – and It's Not Yours, Either.” Vlkerrechtsblog, November 5, 2020.

Zhao, Yun. “Space Commercialization and the Development of Space Law.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Planetary Science. Oxford University Press, July 30, 2018.

Authors

Science and Technology Innovation Program

The Science and Technology Innovation Program (STIP) serves as the bridge between technologists, policymakers, industry, and global stakeholders. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

The Role of Satellites in 5G Networks

About Across Karman