THIS IS AN UNEDITED TRANSCRIPT

Hello, I'm John Milewski and this is Wilson Center NOW, a production of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. My guest today is Benjamin Gedan. Benjamin is director of the Wilson Center's Latin America program. He joins us to discuss the latest from Venezuela, where Nicolas Maduro continues to cling to power in the face of international opposition and an almost universally held belief that he not only lost the last election, but lost it decisively.

Benjamin, let's begin there. Is there I'm being fair. When I worded things the way I just did are attempting to be fair. But is there anyone anywhere who believes that Maduro actually won the vote count? No. There's very little ambiguity that would actually happen in the election. Oddly, given that it's authoritarian state, the election was managed in a fairly professional and transparent way until it wasn't and a false result was announced.

And so there's quite a bit of evidence about what happened. There was the turnout that was pretty clearly motivated by the Democratic opposition and this desire for change. We had seen signals before the election. Not only did polling show overwhelming support for political change in Venezuela, but there was an informal opposition primary that had an extraordinary turnout. And then the opposition itself managed to get its hands on these actors, this physical evidence from the voting machines throughout Venezuela, not all of them, but enough of them to show overwhelming support for the opposition.

In retrospect, was it foolish to suspect for a second that Maduro would actually accept the actual results? Well, look, I think the fact that the election went this far was advantageous for the opposition and for the international community. It's why we're talking about Venezuela right now. It's why the international community is thinking about ways to pressure for a democratic transition.

It's why there's no question, even within Venezuela, about the support or lack of support for the authoritarian regime. So I think there was a lot of value in this exercise. Should we have thought the government might accept the result? Look, I think most people who were following this process were quite skeptical from the start, but thought that there would be some value in going through this process no matter what.

And if there was a remote possibility that the government was willing to accept it, that it was worth a try. What's the situation on the ground currently in terms of the opposition, in terms of protests? Are there is there any recourse available? The really heartbreaking situation in Venezuela right now is that there is no option for affecting the conduct of the government or the future leadership of the country.

And worse than that, we see a system that already was authoritarian and repressive, has turned into a human rights nightmare. You have Operation Knock, knock door to door efforts to root out supposed opposition. You have almost 2000 political prisoners, including many children. You have, you know, protesters killed. You have a situation where the winning candidate, presumably the president elect, now has fled and is living in Spain.

It's pretty devastating. You have seen very courageous public protests. You've seen the opposition remain united under extraordinary pressure. But clearly the government has full territorial control and has full control over the military and the security services. The intelligence services and its ruthlessness means that it is able to keep this population under control at gunpoint. You mentioned Minister Gonzalez in exile in Spain.

Is does he have any role in opposing the government of Maduro? Well, he could. He, again, by all accounts, is the president elect. He is the person that a vast majority of Venezuelans have turned to as their future leader. And that's excluding the nearly 8 million Venezuelans outside the country who, if they could have voted, clearly would have voted for him as well.

So he has a great deal of legitimacy. He doesn't have a tremendous platform right now, having left Venezuela. He's not someone who was a lifelong politician. He was a career diplomat. He's a rather low key individual, not all that charismatic. And so, no, I wouldn't say that he right now is kind of the beating heart of the Venezuelan pro-democracy movement.

Fortunately for that movement, Maria Corina machado, who was the main figure, the winner of the opposition primary but disqualified from running, remains in Venezuela. She's living in hiding, but emerges for public protest, is very active in international interviews and in mobilizing global support. She remains active. And so I think for now, that's the only hope to keep this effort alive.

Sounds pretty dangerous that she remains in the country in hiding. It sure is. I mean, the reason that Gonzalez left is because he was living in fear of persecution, of arrest, of ending up one of these many political prisoners, these arbitrarily detained opposition figures. And it's not hypothetical, as I said. Nearly 2000 political prisoners. You have several former campaign workers who have been holed up in the Argentine embassy.

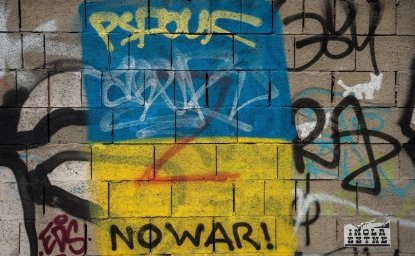

The Venezuelans had threatened to raid the embassy and to remove them forcibly. The situation is quite scary. So have the protests largely been quieted as a result of this crackdown? They are not nearly as large nor national in scope, nor sustain as they need to be to bring about the kind of change we've seen recently in Bangladesh that we've seen in Ukraine in different moments that we have seen in Tahrir Square in Cairo.

The kinds of protests that have to happen in Venezuela in order to shake the foundations of this government are not occurring. And understandably, given the number of Venezuelan opponents of the government who have fled over recent years, a quarter of the population. And given the state of terror. You had an international human rights organization. Describe this as state terrorism occurring right now in Venezuela.

So though that public protest is necessary to bring about political change, it's really understandable that it isn't happening at the level that's necessary to create conditions for new negotiation. Benjamin, talk to us about sanctions and other external pressures. About a week ago, the US announced a new round of sanctions. Are they getting any traction? Are they having any impact on this government's ability to remain in power?

The international community is really struggling with what kind of response is appropriate right now. Sanctions have been attempted. Venezuela really at an unprecedented level over many years, and they didn't produce the kinds of political change that they were pursuing because of that at least for now. I think the U.S. authorities are skeptical about a sanctions forward approach, meaning hoping that strong economic punishment, individual sanctions would be sufficient.

That said, there's enormous political pressure in the United States and also internationally to impose some punishments on the government for its conduct in recent weeks and months. That's why you saw some individual sanctions imposed on members of the Supreme Court, the security services, but not a re-imposition of sectoral sanctions. The other fear is that it'll worsen this migration problem.

And so, you know, a lot of what has gone wrong in Venezuela, most of it is a function of poor governance, public corruption, bad management of the state oil industry. But some of what has gone wrong is a function of international sanctions, and that has been partially responsible for migration. I want to follow up on both of those things.

The migration issue and also the sanctions on the sanctions. Well, how does a government like this survive? I mean, we've seen it with Russia, right? A lot of back doors. A lot of countries willing to help, whether it's North Korea, China, whomever. So it takes the edge off the sanctions, certainly, if not, makes them completely irrelevant or ineffective in the case of Venezuela and the Maduro government.

Who are the external actors who are propping him up or helping him from the outside? Yeah, I mean, scholars have thought a lot about what works and doesn't work with regards to sanctions. And I think we've learned some lessons that might or might not be applied in the Venezuela case. We've learned that they're more effective if they're multilateral, if they're international, if there's a consensus in the international community with Venezuela, there's not China, Russia, Turkey, Iran.

Lots of major international actors have assisted Venezuela in circumventing these sanctions. We've also learned that they get less effective over time. These sanctions in Venezuela have been in place for many years and the Venezuelans have adapted to it and have found ways around it. We've also found that if the objective is regime change, as it often is in Venezuela, that it's very difficult to persuade a government to pursue a different course of action, whether, you know, changing behaviors and other ways particular policy disagreements, maybe sanctions could function.

So for all these reasons, Venezuela has often been a case where sanctions are inadequate and they fail. And I think that is the reason we're right now. Sanctions are not seen as the ultimate solution here. And on the migration question and the impact on neighbors, Colombia in particular has seen quite an influx sharing a border. What is this doing to regional stability?

Yeah, I mean, the Venezuela issue really has become a regional crisis. In the United States, we think about it with its impacts on U.S.. Southwest border challenges. The reality is of these more almost 8 million Venezuelans who fled, more than half of them are in Latin America. 3 million or so are in neighboring Colombia. You have 1.5 million in Peru.

You have Chile affected. Northern Brazil is affected as far south as Argentina and Uruguay. So it's a real regional challenge. And yes, there are fears that if things go even worse right now in Venezuela, you'll see another surge of people leaving. You had polling before the election that was pretty explicit and asking Venezuelans if there isn't political change, will you leave?

And the numbers were terrifying in terms of the number of Venezuelans who said, yes, I will not stay in this country if there isn't political change. So I think that is why you've seen even governments that had historically been more aligned with this Chavista leftist movement, skeptical about whether they should go along with these fraudulent results. I'm thinking of the governments in Brazil, in Colombia, in Mexico, none of whom have recognized the results so far.

And will that pressure matter? Not so far, right. It's not clear how much pressure is coming from these governments. I think the significant they haven't recognized the result. They haven't said they would attend an inauguration in January. On the other hand, it's not clear yet that they're using the relationships, the influence they still have in Caracas to bring about political change.

So far, there's absolutely no sign whatsoever that they have the power needed to nudge Nicolas Maduro out of power. Another bit of new news is these arrests that were made recently. Six foreigners, including a U.S. Navy member of the U.S. Navy or a former member at least of the U.S. Navy. The Justice Department has rejected claims of any CIA involvement in an alleged plot to kill Maduro.

How much do we know about this? Is there any reason to suspect that the claims from Venezuela could be true, or is this just another example of the regime cracking down and using creating enemies from afar? We know very little about this, and so I don't have any particular information about who these individuals were and who, if anyone, externally was organizing them.

What I will say is it be very surprising that at this moment of great tragedy, but also some promise of political change, that any international actors would risk something like that? I think what's fundamentally true about the regime is many authoritarian regimes is they want to distract, they use disinformation, passion, and they often want to portray themselves as these kind of progressive leftist martyrs fighting the imperialist United States.

That's why it has been so critical to see the leftist government in Spain opposing this electoral fraud. The three major governments in the region I mentioned not recognized in the election. Strong messages coming from the leftist government in Santiago, Chile, which has said from the very beginning that this fraud was apparent, that this is an authoritarian, abusive regime and that Latin America, no matter what ideological colors in the capital, must be fighting against this process in Venezuela.

That is a noticeable difference this time around, right? The countries that haven't either turn the other cheek or or quite the opposite have been vocal in their in their criticism. But you're saying that that's not moving the needle. So that raises the question, what can move the needle? Is there anything that the U.S. or other actors can do to put pressure on Maduro to, you know, facilitate change?

Yeah, I mean, I hate to be too resigned to another six years of authoritarian rule in Venezuela. I do think for us to have sensible policy conversations, we have to recognize the limits of U.S. influence. In this case, as we talked about earlier, the sanctions regime was not effective. There was an effort made to recognize of a different individual, Juan Guaido, as the president of Venezuela for several years within 50 countries, signed on.

It didn't change life on the ground. There was this extraordinary unity in the opposition, a mobilization, an electoral attempt to remove this leader. It also didn't work. We have had no luck trying to create distance between some of these patrons outside Venezuela who've been propping up the regime, namely China and Russia, but also Iran, Turkey. And so I think we do have to approach this in two ways.

One is to recognize there is some opportunity right now to be creative, to be unified, and to mobilize international efforts, but also to recognize the limits of our power and the the way that countries often really changes from within. Right. And so do we have any sense that there's any chink in the armor of Maduro and his control of the military or other actors?

I think what we've seen in transitions to democracy is that they're unpredictable. They often happen in moments where no one expected it. You know, on paper, I think Venezuela is vulnerable to that. Conditions are miserable. A quarter of the population has fled, as we discussed earlier. You have the military elite bought off by the government. But the rank and file in the military and in the security services suffer like all other Venezuelans suffer from all the problems, not having sufficient access to medical services, to medical goods, to basic food products, to running water, to electricity consistently.

And so, yeah, there's a lot of potential fractures in Venezuelan society. But to this point, we have not seen any of it coalesce, in part because of the outflows, in part because it's an oil economy. And so even under sanctions generate sufficient revenue to buy off the actors in Venezuelan society who need to remain loyal. Is it impossible?

No. And I think right now there are some pressures on these elites that there might not have been before the election process because they no longer can pretend that this is not a dictatorship. They can no longer pretend that we're in the early period of Chavismo in Venezuela, where in fact it was a very popular movement elected. It would win referenda to change the Constitution.

There was this period where this government, they're not friendly to the United States, was seen positively in Venezuela. Again, it governs now at gunpoint. Can continue to do that indefinitely, maybe. But I think that is a change dynamic in Venezuela. Well, one final thought on any hope for change. A lot of what we've talked about, including what you just described, sanctions certainly fall into this category.

They don't provide immediate gratification. It takes time. Is there any timeline, the most hopeful timeline where pressure circumstances, the conditions in the country could lead to change? Not from sanctions, unfortunately. I think that experiment was attempted. As I said, over time, the sanctions are less influential now, more effective. And I think what we've seen in Venezuela is that it created an economy and a political system that can survive that kind of economic isolation with support from some key international actors.

I think right now probably is your moment of maximum potential for change. And it isn't something that if you let it marinate for months or years, you're going to have a greater opportunity. In fact, quite the opposite. The regime consolidates it creates and buys the loyalty of key actors. It exiles figures like Nuno Gonzalez. It takes the time to isolate or buy off members of the opposition to create fractures and frictions and divisions.

And so, no, I think right now there's a real sense of urgency in the international community to do something to bring about change. If you wait too long, I think you'll find the dictatorship is once again solidified its hold on power. Yeah, chronic conditions don't change until they reach an acute stage. Right. You have to. The fever has to break.

Benjamin, thank you, as always. Very informative. Appreciate your insights. Thanks for the opportunity. We hope you enjoyed this edition of Wilson Center now and that you'll join us again soon. And if you'd like more information on Venezuela or all the various topics that are covered by the Latin America program under the leadership of Benjamin Gedan come to the Wilson Center at the top of the web page, you'll see a programs tab where you can find the Latin America program.

Thanks for joining us. Hope you'll join us again soon. Until then, for all of us at the center, I'm John Milewski. Thanks for your time and interest.