Q: Describe your background and what brought you to the Wilson Center.

I am trained as an historian of the Soviet Union and specialize on the Stalinist period. However, because I teach at a small liberal arts college with superb students, I often create new courses outside my specialization on their recommendation. Thus, I also teach the Holocaust, for which I trained with Omer Bartov at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, global refugee history, an oral history course with local Bosniak refugees, and most of modern Europe. The preparation for new courses like this takes a lot of time away from research, but it gives me a comparative view that I feel makes me a better scholar.

This is my third tour of duty at the Wilson Center in the Kennan Institute. Former director Blair Ruble was an outside reader on my dissertation at Georgetown about the reconstruction of Sevastopol, Ukraine after the Second World War. As I began to transform the dissertation into a book, he suggested I apply for a grant. Thus, both From Ruins to Reconstruction and my last book, Stalin’s Niños benefited from Title VIII support. The first book will soon be released in an open-source Ukrainian edition as Від руїн до реконструкції. Міська ідентичність у Рад Севастополь після Другої світової війни.

Q: What project are you working on at the Center?

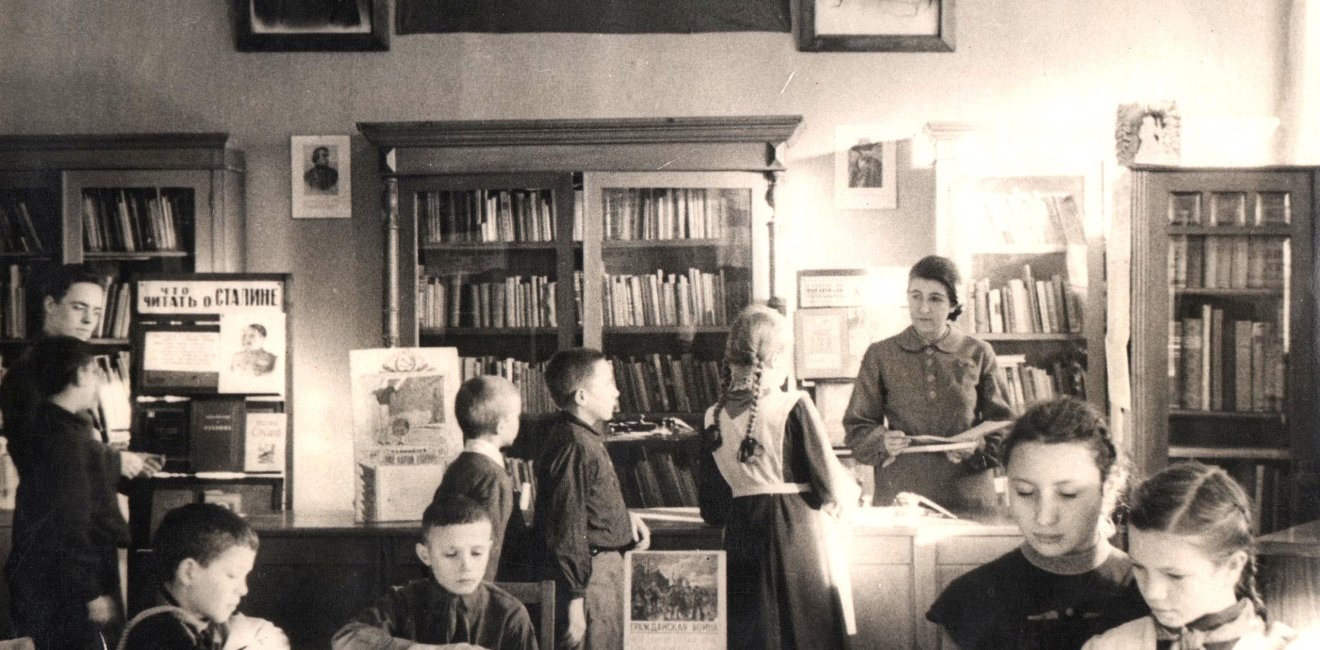

At the start of this year, I began work on what I hope will be a new book on modern childhood in the interwar period in the USSR, Nazi Germany, Mussolini’s Italy, and the United States. By comparing childhood in four distinctly different political ideologies with varying degrees of executive power, I want to explore what is part of a more general turn toward viewing children as a state resource—mother, soldier, worker—and which characteristics are inflected by national cultures and political ideologies.

Q: How did you become interested in your current research topic?

One of my students suggested the current project. I teach a course on Hitler, Stalin, and Mussolini and occasionally bring in FDR’s New Deal to contextualize the dictators. I always lament that I never have a textbook I like. In a recent iteration of the course a student told me to write it. I sketched out some ideas and realized the course material was too big for one book, so I am limiting it to childhood because that was the subject of my last book on child refugees of the Spanish Civil War who were raised in the USSR.

Q: Why do you believe that your research matters to a wider audience?

Quite frankly, the shift we have seen in recent years to more extreme right-wing governments has seen a return to drastic government intervention into childhood to create their ideas of a national/patriotic citizen in the making. Just think of the culture wars in the classroom in the US as but one example. Putin’s regime has been one of the most interventionist in militarizing the youngest Russians. He has stolen so many ideas from Stalin that it is important for us to understand both the causation and the effects of those past manipulations of childhood.

Q: What is the most challenging aspect of your research?

Children don’t leave sources! Children’s history—history told from the child’s perspective—is by far the most difficult, so most of us in this field call ourselves historians of childhood instead. We study the adult interventions into childhood (e.g. education, family law, children’s literature, youth groups) and then, when available, add the scant letters, memoirs, and oral histories from the children themselves. It is much easier to study famous people and their famous colleagues who leave abundant documentation. Historians of childhood don’t have that luxury, so in my case, at the Kennan I started studying things like children’s games, riddles, crosswords, etc. in children’s magazines to see what type of child Stalin’s regime hoped to construct and comparing to memoirs and oral histories to see how Soviet citizens understood Stalinist play.

Q: What do you hope the impact of your research will be?

Most importantly, I simply want readers to take seriously the history of childhood. It is the one moment in time we all share. Some of us don’t make it to adolescence or adulthood, and so much of what we become is shaped in childhood by parents, teachers, religious institutions, youth groups, and play. So why do we ignore the most formative period in our lives? This can reveal a great deal about the people who become future leaders, artists, innovators, and more. If we look across the artificial boundaries of countries, we can see that many states’ policies toward children are quite similar and exist on a continuum, not in opposition to each other.

Author

W. Gibbs McKenney Chair in International Education and Professor of History, Dickinson College

Kennan Institute

After more than 50 years as a vital part of the Wilson Center legacy, the Kennan Institute has become an independent think tank. You can find the current website for the Kennan Institute at kennaninstitute.org. Please look for future announcements about partnership activities between the Wilson Center and the Kennan Institute at Wilson Center Press Room. The Wilson Center is proud of its historic connection to the Kennan Institute and looks forward to supporting its activities as an independent center of knowledge. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region through research and exchange. Read more